What? So What? Now What?

What? I will start with a brief annotated bibliography of the two assigned readings:

Friesen, N. (2009). Open Educational Resources: New Possibilities for Change and Sustainability. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 10(5). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v10i5.664

Friesen dives deeper than the philosophical arguments that support Open Educational Resources, and considers factors that influence OER project’s longevity and financial sustainability. He holds the MIT Open Courseware Initiative up as a successful example of an OER project, and argues that increased student recruitment and marketing have contributed to the project’s success. I appreciated the realistic analysis of the success and failures of OER projects, as evidenced by the number of collections from January of 2009 that are no longer in operation. Collaboration between the technology experts, business and marketing experts, the educational institution, and the individuals to whom the resources are intended is imperative for an OER to be successful. In addition, reflective practices and continued discourse between stakeholders is necessary for longevity.

Friesen begins his article by defining open educational resources as “the open provision of educational resources, enabled by information and communication technologies, for consultation, use and adaptation by a community of users for noncommercial purposes” (UNESCO, 2002, p24). On December 2, 2019, a blog post by David Wiley points out that a recent decision by UNESCO’s members has limited the use of OER to simply accessing the materials, rather than retaining OER. I am struggling with how to interpret the readings this week when the definition of OER is unclear, and therefor the possibilities available to me through accessing those resources are limited. I already have access to an immense amount of material. Being able to copy, edit, and make educational resources my own is what holds value for me. Otherwise, it is simply a text book that is available online.

Conole, G., & Brown, M. (2018). Reflecting on the Impact of the Open Education Movement. Journal of Learning for Development – JL4D, 5(3). Retrieved from

http://jl4d.org/index.php/ejl4d/article/view/314

Conole and Brown inspect the rise of the Open Education Movement (in particular e-textbooks, MOOC’s and OER) from the perspectives of learner, teacher and researcher. There is some ambiguity in the introduction as to what constitutes Open Educational Resources, however definitions of OER often include the freedom to use, reuse and share free digital content. I envision a staircase with limited (perhaps by student number) online free access on the bottom step, and additional attributes adding stairs until one reaches the top of the staircase: Free, unlimited, access to educational resources with the ability to use, adapt and distribute open material. Conole and Brown outline the benefits of e-textbooks and MOOC’s by considering relevant case studies at the post secondary level, and then describe barriers and enablers to OER and MOOCs. Unfortunately, I did not find any of their reflections ground breaking although I did appreciate the summary. In the conclusion it is revealed that the author’s do not predict that open practices will replace traditional educational offerings, and that the most potential of OER lies in offering a varied learner experience, challenging traditional educational offerings, and providing free resources for learning.

Throughout the reading I can’t help but question the potential depth and breadth of the Open Education Movement in post secondary education. Even if open online learning was afforded the same or similar credentials as traditional higher education, would it drastically change who aspired to pursue higher education? I can only speak to the North American situation, but in my experience a student with drive and potential has access to thousands of dollars in scholarships and bursaries to help them achieve a post-secondary education. Might the most difficult barriers to higher education be childhood trauma, emotional stability, a difficult upbringing or the lack of positive and encouraging role models? To tackle these barriers would take moving mountains. Perhaps providing OER is a step in the right direction, or perhaps we should be focusing our time and money on equaling the educational playing field by tackling the really tough stuff.

When considering “So What” and “Now What” I will focus on OER in BC Public Schools.

So what?

What can be learned by reviewing the successes and failures of Open Educational Resources? What new possibilities exist for OER and how can we improve the sustainability of OER?

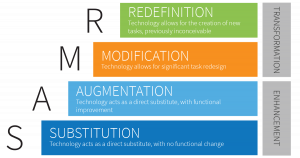

By looking to projects such as MIT Open Courseware Initiative and Creative Commons we can see the attributes that have contributed to success and longevity of OER, however we must also considering failed OER projects. A continued source of funding and a strong business model, a clear vision, diverse educational material, ongoing content development, and marketing were noted as important contributors for success. For my specific purposes as a senior science teacher, I can see that the benefits for OER in public education could be far-reaching, however the above noted attributes must be in place for successful implementation. Also of utmost importance for me is that an OER project in public education is not simply allowing access for students and/or teachers, but is affording the opportunity for the 5 R’s for everyone: the ability to retain, reuse, revise, remix and redistribute the information.

Have my opinions or perspectives changed after doing the readings?

I am a little more skeptical of the potentials for success of OER in public education for the following reasons:

- First of all, it would likely not be truly ‘open’ as it would be intended for teachers, students, or for families of students in particular school districts. However, it could still offer many of the positive attributes of an OER for its users.

- Public education is a publicly funded service and employees of public education are unionized, which has not (in my opinion) contributed to public education exemplifying a strong business model.

- Financially, it would need to be presented in such a way that educators and schools would be convinced to do-away with textbooks, hence providing a cost savings that could contribute to the OER project.

- The sheer number of educators that could contributors to such a project would require a highly organized LMS.

- Maintenance of the project. By whom? Would this be a provincial project with district representatives? Who would be responsible for the implementation and maintenance of the project?

- Collaboration between stakeholders. The introduction of a new directives (for example, new technologies, new curriculum, MyEd, cultural orientation and inclusive education, just to name a few) have generally not been communicated well to employees and have generally not been supported by adequate input, time and training.

Now What?

How can I take what I have learned and apply it to my teaching practice?

Even with all the obstacles that face OER projects, I am still optimistic that such resources will be made available for BC public schools and the BC public school curriculum. My role in the implementation of such a project would be to invest the time and effort into orienting myself with the project, contributing worthy content, and investing significant time restructuring my courses for continued improvement, relevance and interest. By learning from others’ mistakes, learning from our own mistakes, and building on our successes, there is certainly potential for OER to be a valuable part of BC’s Public Education system.

I have and will continue to encourage my students to access available on-line materials that currently exist in order to help them be curious and independent learners. Should I also be making my lessons and teaching materials open and on-line? Teachers pay teachers (although not free) and creating a teacher website are two ways that I could offer my personal teaching resources to the general public. I hesitate to do this as I adapt and change my lessons and resources each semester. The responsibility of managing my online contributions on top of my current responsibilities is daunting. I will need to spend more time considering this question.